Timeline

Attempts to remove stoats

As sightings increase, so do concerns and NatureScot initiate various trapping attempts with the help of volunteers. Despite some success in South Ronaldsay, not all stoats in Orkney are trapped and they subsequently spread.

Stoat impacts assessed

NatureScot commisions a report looking at the potential impact of stoats on Orkney's world-renowned native wildlife. Published in 2015, it finds that stoats are a serious threat and an eradication is the only way to safeguard Orkney's wildlife.

Find out more

Partnership formed

NatureScot and RSPB Scotland form a partnership to seek the funding needed for a project to prevent the devastating effects of the burgeoning stoat population on Orkney’s native wildlife. A Technical Advisory Group is created with global expertise including in eradications, gamekeeping and stoats.

Consultation results

The community consultation shows overwhelming support for Orkney’s native wildlife:

- 92% of respondents feel people have a duty to protect it,

- 88% worry about the declines in native wildlife if stoats are not removed and

- 84% support a full eradication.

Trapping trial results

Results show more stoats are caught in traps in moorland and coastal areas, the trap boxes with two entrances are better and eggs are the most effective bait in spring.

Biosecurity dog searches

- Macca - the UK's first stoat detection dog - and his handler Ange come from New Zealand to spend three months checking for signs of stoats on high-risk islands (those within swimming distance of islands with stoats).

- They find no concrete evidence of stoats on any of the other islands but based on their advice additional traps are added to the biosecurity network in South Walls.

Full funding secured

- Orkney Islands Council joins the project as a partner.

- The project secures five years of funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and EU LIFE supported by in kind and financial contributions from the RSPB, NatureScot and Orkney Islands Council. Find about more about the partnership.

Full project begins

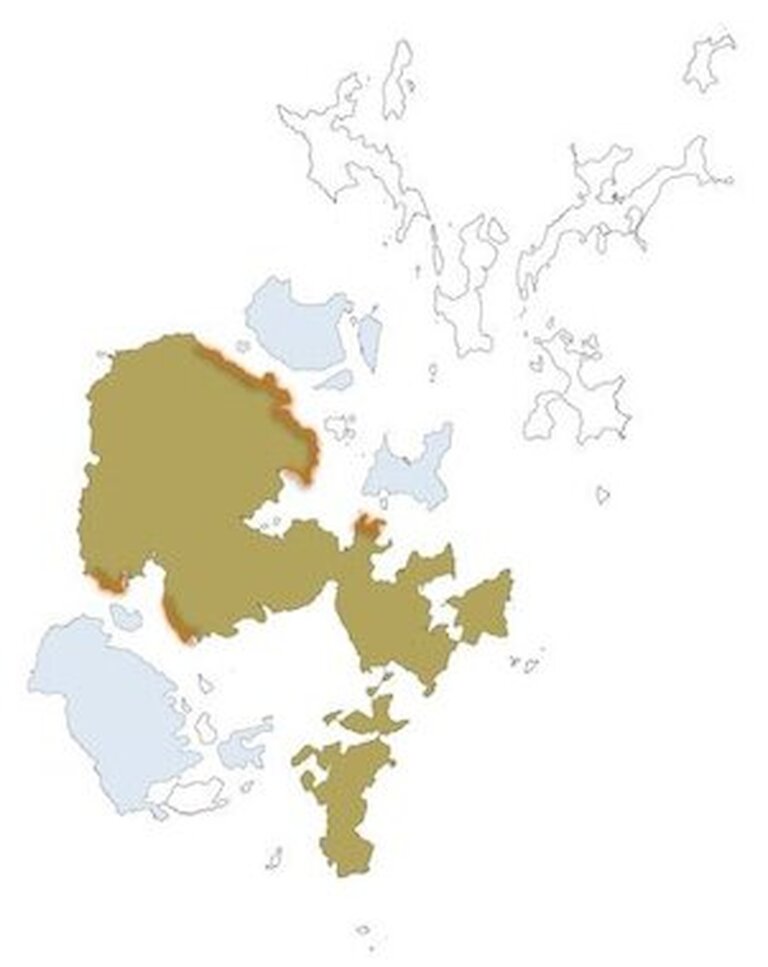

- The first eradication traps are laid across South Ronaldsay and the linked isles and in protected areas on the Mainland. Trap deployment then begins in other areas of Mainland from east to west.

- Biosecurity trap networks are put in place across high-risk islands (those within stoat swimming distance of Mainland) to try to stop stoats spreading

- Surveys for voles and breeding birds undertaken

- First schools visits are carried out

Covid curtails progress

- Traps in East Mainland opened in early March. Deployment begins across West Mainland.

- Covid-19 lockdown stops all project activities until restrictions are lifted. Final traps in East Mainland opened in July, meaning that a whole breeding season is essentially missed.

- This allows the stoat population to rebound from initial trapping efforts.

- Some volunteer trappers trained, but school visits, events and biosecurity workshops with communities still not possible.

Eradication expands

- By March, all traps across West Mainland were open meaning active trapping was happening across the whole trap network for the first phase of the eradication.

- With Covid-19 restrictions lifting, the project's first three stoat detection dogs arrived in spring ready to begin biosecurity checks for signs and scent of stoats on islands believed to be stoat-free this summer.

- Covid-19 continued to effect other project activities particularly school visits, events and volunteer training.

Mop-up trial launched

In 2022, stoat numbers in some areas were reduced enough to begin trialling techniques for the mop-up phase of the eradication. Mop-up is the second stage of the eradication, when stoat numbers have been significantly reduced but the last remaining stoats still need to be removed. Community activities, wildlife monitoring and biosecurity all continue.

The results show that this more active trapping method, which involves using the dogs to identify stoat hot-spots, and responding to public sightings, is highly effective at removing stoats. However, it also shows that there are still too many stoats to move into mop-up.

Application for funding to extend

The project announces that it is applying for funding to extend for a further three years of eradication, followed by two years of monitoring. The need to extend is the result of the delays caused by covid, the unique conditions of carrying out an eradication in such a large and inhabited landscape, and the unusual behaviour of invasive stoats in Orkney. Other options like control, coupled with biosecurity for the stoat-free islands are considered, but they are ultimately deemed impractical and extremely expensive compared to completing the eradication.

With over 5,000 stoats removed, and a tried and tested methodology for finishing the job, the project announces that it is seeking funding from a range of sources.

The eradication ends

With all stoats removed from Orkney, a major operation will be undertaken to remove the trap network. However, equipment hubs and biosecurity staff will be kept in place to keep Orkney stoat free and respond if a stoat appears within the two year monitoring period.

The two year monitoring period ends

With two years of monitoring at an end, and no stoat found, Orkney can officially be declared stoat free! If a stoat is found within this period, it is likely to be within the first year, based on comparable eradication projects. In this scenario, the stoat will be removed, and the clock restarted.

Legacy

There is an active long-term biosecurity plan in place to prevent re-invasion by stoats this includes continued reporting of potential sightings and the ability to respond to potential incursions.

Wildlife monitoring continues to ensure the health and status of Orkney's incredible native wildlife is known and it can be protected from future threats.