Stoats investigating a curlew scrape in Orkney:

Stoats are not native to Orkney and were first reported in 2010. They pose a serious threat to the islands' native wildlife and economy.

Globally, invasive non-native species have contributed to 40% of animal extinctions in the last 400 years. On islands, this number goes up to 60%. Stoats are a major threat to native wildlife in areas where they are not native, particularly on islands where they have no natural predators, and which have large resident bird populations.

New Zealand has no native mammals apart from bats. Stoats were introduced in 1884 to control rabbits with catastrophic consequences. While rabbits remain a problem, stoats contributed to the extinction of New Zealand’s laughing owl, mātuhituhi, and South Island Kōkako. All within 100 years.

Today, they continue to threaten the iconic kiwi. Despite the array of invasive predators in New Zealand, this record has earned stoats the title of “public enemy number one” from the country’s Department of Conservation.

We have a responsibility to ensure the same thing doesn’t happen in Orkney.

What is a stoat?

Stoats (Mustela erminea), along with weasels, ferrets, badgers and otters, are part of the Mustelid family. Typically brown with a pale chest, in winter they can turn wholly or partially white (ermine).

Stoats are up to 30 cm long and are most easily identified by their long tails that always have a black tip and their agile bounding gait.

For more information, look at our stoat identification guide.

Stoats are...

- Skilled hunters

- Stoats are fast, agile and good climbers with very good eyesight, hearing and sense of smell. They are capable of killing prey much larger than themselves.

- They also tend to kill more than they need and store (cache) the rest to eat later.

- Big eaters

- They have very high metabolic rates and need to eat a quarter of their body weight every day (the equivalent to you eating 41 portions of fish and chips daily).

- They are omnivorous eating eggs, chicks, voles, mice, rabbits, hedgehogs, fish, insects and even roadkill, pretty much anything edible and easy to catch.

- Long-distance movers

- Kits can travel over 40 miles when leaving the nest area find their own territories.

- Stoats can also easily swim 3 km or more between islands.

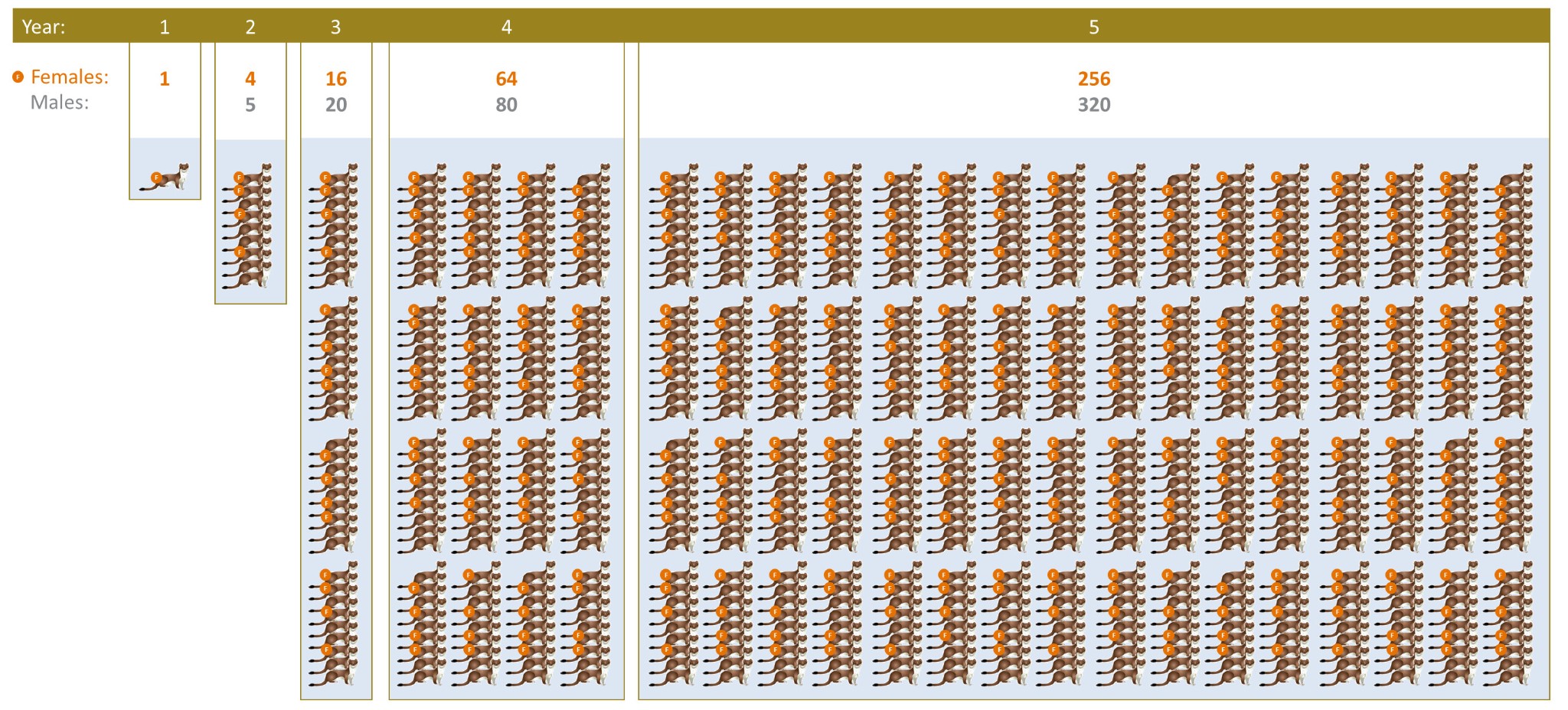

- Prolific breeders

- They have large litters of 6-12 kits (maximum record of 20).

- Females reach sexual maturity very early and can become pregnant at just 2-3 weeks old (when they still are deaf, blind, toothless and furless).

- They also have delayed implantation, which means that a female can be impregnated in late summer and the kits will start to develop the following spring.

Stoats are skilled hunters, need to eat a lot, and are capable of breeding very quickly. Because they are not native to Orkney there's no natural predators on the islands, and the abundance of year-round food in the form of Orkney voles means that their population can boom and then remain high.

This means they pose a significant and immediate threat to wildlife like the Orkney vole, hen harriers, curlews and Arctic terns, as well as businesses that thrive because of our incredible natural heritage.

The threats...

- Threats to native wildlife

Orkney's incredible native wildlife is threatened by the arrival of stoats.

A 2015 report concluded that they pose a serious threat to Orkney voles, hen harriers, short-eared owls and other ground-nesting birds, including red-throated divers, Arctic terns and waders including curlews.

Stoats eat both chicks and eggs. They will also impact hen harriers (the UK’s rarest bird of prey) and short-eared owls through competition for their favourite food – voles – as well as posing a threat to the Orkney voles themselves.

These impacts will become increasingly severe if stoats are not removed and will result in irreparable change to Orkney’s natural heritage.

- Threat to tourism

Tourism is an important part of Orkney's economy. In 2012-13, 142,816 visitors spent £31 million in the county. By 2019-20, this figure had increased to £70 million. With nearly 50% of visitors spending time watching birds and other wildlife, any significant loss of natural heritage will have a dramatic impact on revenue generated from tourism.

- Threats to farming

Orkney has a widespread culture of keeping free-range poultry and there are already reports that some have been injured and killed by stoats. If the stoat population is left unchecked, ultimately poultry will need to be caged in stoat-proof housing with financial implications for landowners.

There are also indirect economic threats. The most significant is the potential decrease in agri-environment contracts. Currently, Orkney farmers get more points because they are in a priority area for wildlife. If Orkney becomes relatively less important for wildlife because of the impact of stoats, this could have a negative impact on the subsidies currently received.

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project aims to safeguard the native wildlife of Orkney by addressing the threat it faces from invasive non-native stoats.