It is not known how stoats got to Orkney; they could have arrived in cargo or they may have been intentionally released as they were in New Zealand to control rabbits.

Frequently asked questions

- 1. How did stoats get to Orkney?

- 2. Why are you removing stoats?

Stoats are not native to Orkney and pose a serious threat to the internationally important native wildlife of these islands. Orkney has the highest density of breeding curlew in Europe, one in five UK hen harriers, and 11% of UK seabirds. This is all despite being less than 1% of the UK landmass. The Orkney vole is a subspecies found nowhere else in the world, and it sustains Orkney’s important populations of hen harrier and short-eared owl. Just one stoat den in Kirkwall was found to contain the carcasses of over 100 Orkney voles.

When introduced to New Zealand in the 1800s, stoats drove three species of ground-nesting bird to extinction within 100 years. Despite the range of invasive predators there, stoats are considered ‘public enemy number one’ by NZ's Department of Conservation because of the damage which they have done to native wildlife. The Orkney Native Wildlife Project has been set up to prevent a similar tragedy from befalling Orkney.

- 3. How are you removing stoats?

The stoats are killed humanely using lethal traps. We do not use live traps. The DOC200 and smaller DOC150 traps we use are housed in specially designed trap boxes. These ensure the traps operate humanely and minimise the chance of catching other animals. Roughly 80% of these trap boxes contain two traps. There are currently approx. 8,000 trap boxes deployed across Orkney. For more information on eradication operations click here.

- 4. How can you justify killing stoats?

We understand that some people will never want to see animals killed and we respect that view. However, the risk to Orkney’s native wildlife is too severe not to act. Doing nothing would have risked huge population declines in iconic native species, including the Orkney vole, short-eared owl, and hen harrier, and done irreparable damage to Orkney’s natural heritage. Whether intentional or accidental, stoats have arrived in Orkney through human activity, and we have a responsibility to restore the islands to stoat free status.

Translocating stoats is unfortunately not possible due to their high metabolism and the stress it would cause them. What is more, releasing thousands of stoats into any area of mainland Scotland would likely have a disastrous effect on the local ecology. This would manifest as a severe decline in prey populations, which would ultimately threaten native stoats in the area. Eradication is the only way to protect Orkney’s internationally important native wildlife and the parts of the economy that depend on it, and using lethal traps is the most humane way to do it.

- 5. How do you prevent the traps catching other animals?

We take all possible measures to prevent other animals from getting killed. The trap boxes are designed, and the traps are set, to prevent other animals from being caught and we use stoat specific lures. Each trap box has a small external entrance hole (reduced further with a wire tie) and an offset inner entrance that make it harder for larger animals to reach into the trap. The traps are set to spring at 100g, meaning lighter animals such as mice, voles and shrews should not spring the trap. On our trap checks, we sometimes find the bait is missing but the trap is still set, indicating that smaller animals are entering the box without triggering the mechanism. The only animal we cannot minimise catching is brown rats. This is because of their similar size, diet, and weight to stoats. While we do occasionally catch other species, this number has no bearing on the overall population. The same cannot be said for unchecked stoat predation.

- 6. How will you make sure the eradication will succeed?

Out of the 1,550 eradications across nearly 1,000 islands since 1872, 88% have been successful. While Orkney presents some unique challenges, the project is following the data, and this shows that the eradication can be achieved using our current methods.

In 2015, before the project started, the feasibility of removing stoats from Orkney and preventing them returning was assessed by a world-leading stoat eradication expert. The review concluded both were feasible and that eradication should be attempted. We then tested trapping methodology in Orkney as part of the development phase of the project by running trapping trials to try out different stoat traps, baits, lures and various monitoring methods.

These findings formed the eradication plan which was reviewed by an independent Technical Advisory Group (TAG) as well as the International Eradication Advisory Group. TAG members bring expertise covering stoat ecology, trapping and eradications enabling them to provide specialist advice and support throughout the project. Our trapping team are also experienced with a mixture of gamekeeping and eradication skillsets.

- 7. How will you ensure that once stoats are removed, they won’t return?

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project is committed to supporting the long-term biosecurity of the islands. This includes working with communities on islands without stoats to develop biosecurity plans to prevent stoats spreading there while the eradication is taking place and producing a long-term biosecurity plan for Orkney to ensure that stoats do not return once the eradication is complete. Islands like Hoy, Rousay, and Shapinsay all have dedicated biosecurity response hubs, and work is ongoing with freight companies to check cargo coming into Orkney.

- 8. How are you using dogs to find stoats?

Stoats are notoriously difficult to detect, particularly when their population is at a low density. The most efficient way to work out whether stoats are present is to use specially trained conservation detection dogs to systematically search areas responding to sightings we receive. Following the same high standards as dogs that are used to detect drugs and bombs, our dogs have been rigorously trained to identify signs and the scent of stoats and to indicate this to their handlers. They are trained not to try to catch stoats, only to indicate their presence. They are also trained not to react to other animals including livestock. The stoat detection dogs are used on the frontline of the eradication to indicate where stoats are present, and to search stoat free islands when a possible stoat sighting is reported.

- 9. Couldn’t stoats be helpful if they control numbers of rats and geese?

There is no evidence that stoats are an effective way to control Orkney’s rat population. Experience from New Zealand shows non-native stoats didn't control the rat or rabbit population there, but they are implicated in the extinction of three bird species. A UK study of the diet of stoats found evidence of rat in only two of 570 stoat stomachs. And the number of stoats caught in our traps suggests Orkney’s rat population has not been affected by the introduction of stoats.

Although stoats may eat the eggs of greylag geese, they are highly unlikely to have any significant effect on greylag goose numbers as their eggs are only available as a food source for a short time each year and parent geese will defend their nests. Stoats will choose easier prey such as Orkney voles and will have a devastating effect on Orkney’s native wildlife if not removed.

- 10. How has the Covid-19 pandemic impacted the project?

The Covid-19 pandemic and resulting lockdown restrictions meant that we had to pause all trapping operations for nearly three months from 23 March 2020 as this was not deemed essential work. During this time, we were unable to check and deploy traps. For over a year the project couldn’t take part in school visits, community events and biosecurity planning and the arrival of our conservation dogs from England was delayed. The timing of the lockdown coincided with the breeding season for stoats, so we missed catching family groups before young became independent and dispersed which undid progress that had been made by allowing numbers to bounce back. When we resumed operations in June 2020, we had to adapt how we worked including trappers not sharing vehicles which has made trap checking slower than before.

- 11. Where did you get funding from?

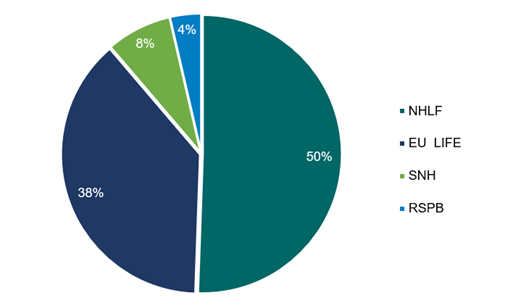

In October 2018, the project secured £3.5 million of funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and £2.6 million from EU LIFE. These grants make up 88% of the funding with the rest coming from in kind and financial contributions from partners.

NHLF

£3,488,000.00

EU LIFE

£2,636,597.00

SNH

£526,000.00

RSPB

£249,716.43

Following the setback and delay caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the project was extended by a further year. The National Lottery Heritage Fund has provided 75% of the extra funding needed from an emergency grant.

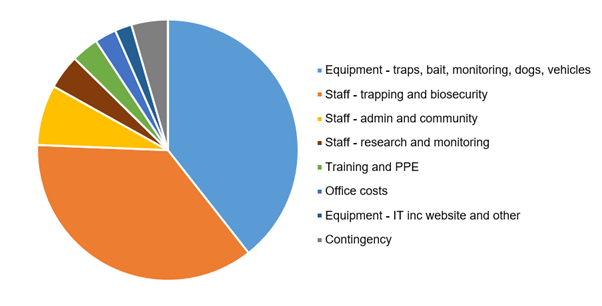

- 12. What is the money being spent on?

- 13. Will the result justify the expense?

A 2015 report concluded that stoats will have a long-term and massively damaging impact on Orkney’s native wildlife if left unchecked. Orkney has the highest density of breeding curlews in Europe, one in five UK hen harriers, and 11% of UK seabirds. All of this is threatened by invasive stoats. In a global biodiversity crisis, places like Orkney are a bastion for native wildlife. If we cannot protect them, we have little chance of restoring these species to their natural ranges across the UK.

What is more, Orkney’s native wildlife is hugely important for the local economy. Orkney has a thriving wildlife tourism industry. Visitors spent £70 million in 2019-20, with 46% of visitors engaging in wildlife watching activities. In 2019, farmers in Orkney received £2.35 million in Agri-Environment Climate Scheme payments (9% of all Scottish payments despite being just 1.3% of its land area). These payments are at risk if wildlife like curlews and hen harriers decline in Orkney.

- 14. What happens when I report a stoat sighting?

Your stoat sightings can tell us a lot about the movement of stoats! As we prepare for the project's final phase to remove all stoats from Orkney, we are counting on everone to report their sightings as quickly as possible! You can learn more about what hapens when you report a sighting here.